A new roadway of smooth concrete was completed between Follansbee and Wellsburg. The dangerous curves on the road were eliminated.

- Steubenville Herald Star, “Will Finish by Late October.” September 11, 1925, p. 24.

A new roadway of smooth concrete was completed between Follansbee and Wellsburg. The dangerous curves on the road were eliminated.

Oak Grove cemetery is located on farm land purchased from J. S. Philabaum. First to be buried in the cemetery was Anna Boffo, the infant daughter of Alex and Theresa who moved to the area now called Hooverson Heights in 1920. My Father, Frank S. Chorba, remembered graves being moved by horse drawn wagons from the Bates farm area north of Follansbee to Oak Grove. He recalled seeing a broken coffin with red hair peaking out. Prior to Oak Grove, no public graveyard was located in Follansbee. That is why earlier burials occurred at Brooke Cemetery in Wellsburg. Today, Oak Grove symbolizes the memory of hundreds of citizens whose courage and spirit lives on in Follansbee.

Early Earl Wendt family burial. Notice Alleghany Street in the background.

Many Mom-Pop mines existed in the early years of the city. In fact, many folks simply dug coal out of the hillside in their back yard. However, newspaper sources do record some coal companies that were near or in Follansbee. They include:

Mark Harlan on Tom at Fireside Fuel Mine. Photo-1954.

Cliftonville Mine coal camp 1930s.

Manager of Fireside Fuel Mine 1954.

1923 – Ku Klux Klan in Follansbee

As Follansbee grew into a mill town, the newly arrived immigrants, primarily Catholic peoples of central and southern Europe, clashed with the Protestant population. The city became divided as new immigrants settled in the city’s lower end. (See .“Orchard” and “Lower End” on timeline)

In addition, the Ku Klux Klan was a major social force even before the 1920s targeting hostility toward Catholics, and especially colored families. In October 1916, following a wedding and reception at a home on Main Street, about 30 local boys, all dressed as “The Ku Klux Klan,” took charge of the groom and paraded the street, with red lights burning brightly.” The Steubenville Gazette reported that this was becoming the usual custom in Follansbee.

In October 1923, a dozen or more black families were preparing to leave Follansbee because of a warning painted on a tin mill fence facing their section of town. “The message was painted shortly after two fiery crosses were burned on the hill overlooking the colored section.” The Ku Klux Klan was credited with warning all blacks to leave immediately, according to the Pittsburgh Courier. “Race citizens for years were excluded from the town. But recently many colored families were brought in by industrial concerns.”

American sociologist, James W. Loewen classified Follansbee as a “Sundown Town,” where Blacks were forced (or strongly encouraged) to leave prior to sundown in order to avoid racial violence perpetrated by majority white populations. Loewen maintained that Follansbee kept out African Americans “for years” before the early1920s.

Steubenville Weekly Gazette, “Follansbee,” Oct. 12, 1916, p.2.

The Pittsburgh Courier, “WVa Families Is Laid by Klan, “ Oct. 24, 1923, front page.

James W. Loewen, “Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension of American Racism,” (Simon & Schuster, 2006), p. 71.

The annual Jubilee served as a means to raise funds for the city including Pastime Park. The events included motorcycle and auto races, water battles between fireman from local towns and boxing shows. The boxing matches were on Main Street between Ohio and Penn. One hundred year old Joe Prest recalled that the motorcycle and car races occurred on Virginia Avenue. There were many other events to entertain the hundreds of people attending. The Dokie band and degrce team preformed.

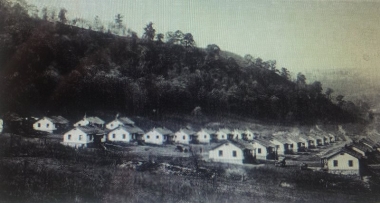

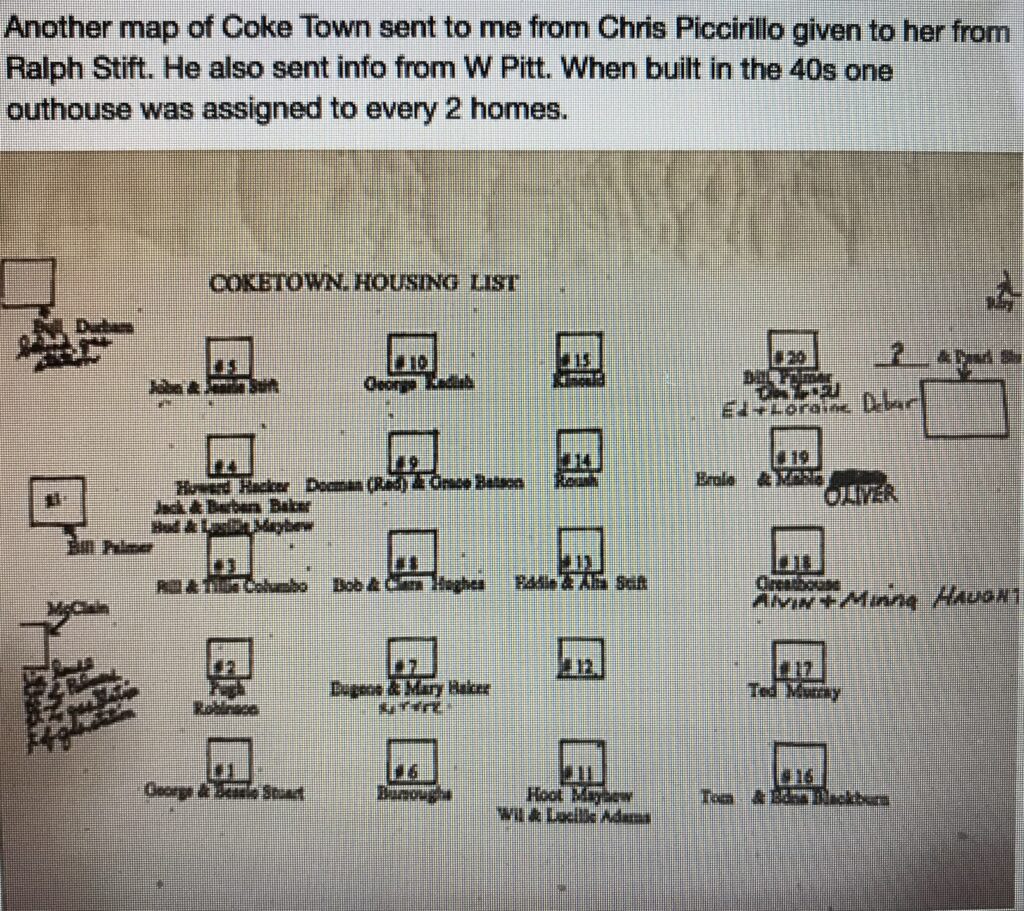

The history of “Coketown” was well documented by Douglas Waugh in his article cited below. The LaBelle Coke Plant was constructed between 1915-1917 and became part of the Wheeling Steel Corporation in 1920. The plant encountered a shortage of local employees and was forced to hire workers outside the Follansbee area. Follansbee was a fairly small community and most of the population was already employed at Follansbee Steel and other factories.

The labor shortage was solved when Wheeling Steel obtained a 600-foot strip of land from its subsidiary the LaBelle Iron Works of Steubenville. The property was ideally situated opposite the Coke Plant on route 2. Wheeling Steel began building a company town with inexpensive housing around 1921. However the actual sale of the land was not official until 1923. Wheeling Steel obtained a number of prefabricated houses that were erected on the new property. Out-of-town employees were quickly hired and occupied the houses. The little community became known as “Coketown.” The houses were arranged in rows of five each. Out-houses and coal storage sheds were constructed, one out-house for every two homes. The new residents paid for their homes through deductions from their paychecks. The plant assumed most of the responsibility for the maintenance of the buildings. In all, there were 20 houses in Coketown.

Locals who remember Coketown will recall the filthy smoke from the coke plant that prevailed throughout the small community. “Coketown women dusted twice a day.” After four decades of unhealthy environmental living conditions and the gradual deteriorating state of the houses, Wheeling Steel gave public notice that the dwellings would be condemned as each house was vacated. The last houses were vacated by 1969.

More than 1,200 shots were exchanged between deputy sheriffs, state police and armed citizens and the suspect, Joseph Jones. The incident started after Jones shot Harry Jones (not related), a Brooke County deputy sheriff. The gunman Joseph Jones then barricaded himself in his home.

The incident began when Deputy Harry Jones and Lee Chambers, Brooke County Sheriff, responded to a phone call from Mrs. Jones that her husband was threatening her. Upon arrival at the Jones residence, Joseph Jones opened fire. Twenty shots were exchanged resulting in Deputy Jones being shot in the leg. Taking the wounded deputy, Sheriff Chambers returned to Wellsburg. Chambers secured six deputes, two state policemen, two machine guns and 10 riot guns and returned to the Jones home in Follansbee. A volley of gunfire met the posse on their arrival. The officers were joined by armed Follansbee citizens as a sensational gun battle began. Machine gun bullets poured into the house. Joseph Jones kept up a steady return fire of over 100 rounds from the basement windows and later the upper floor of the house. When the fire from the house ceased, Joseph Jones was fund wounded and unconscious. He was taken to the hospital. His wounds proved not to be serious.

Even though the bullet was removed from Deputy Jones, gangrene developed and he died of pneumonia on February 18, 1923. Deputy Harry Jones had previously served as a Follansbee Night Lieutenant for a year and a half. He also worked in the Follansbee Brothers mill for 18 years before entering law enforcement. Joseph Jones was convicted of and served time in the State Penitentiary at Moundsville.

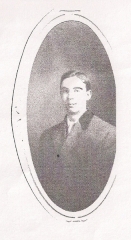

Picture Harry Jones. Photo courtesy of Brooke County Genealogy Society

Traveling thousands of miles, four local boys reached the Pacific coast, traveling overland in a Ford touring machine. The Herald Star reported that William Krager, Louis Dillar, Walter Moyer and Harry Lambing, reached Los Angeles in 27 days. The four men stopped at all places of interest sending post cards regularly. Remarkably, their trip was delayed for only four hours due to breakdowns and tire trouble. Post cards were received daily by relatives and friends who watched with interest their road trip across the country in a Ford. The specific model of the car was not identified by the newspaper.

Also in 1928, 3 adventurous Follansbee boys crossed the country from Follansbee to California. See back side of photo presented here for names and where the photo was taken.

A team called the Tigers was preparing for their first practice session and was endeavoring to arrange an opening game with Weirton. Among the locals stars turning out for the team were Sap Bucey, Jim Cox, Davis, Kasarda, Coulter, Ray Blakley, Soroggins, J. Kelly, Mulroorcey, Smith, Millington, and others. (Some first names were not given. Some names may be misspelled due to poor microfilm copies). The practice sessions were being held at Pastime Park following working hours. The Tigers team was a reorganized version of the Blakley A.C. team of 1920-21.

As football season approached, the town fans were enthused over the fine showing of the team the year before. Now the little school was beginning the new season against the largest school in the state — Wheeling. The cry at Follansbee was “On To Wheeling.” It was the first time the schools would meet. Building on the excitement, the F.H.S. boosters discussed ways to built fan support for the Wheeling game.

The result was the founding of the “Pepper Club.” Their immediate goal was to gain 100 staunch boosters to get behind the team and find ways to promote them on to even better season. The first elected club officials were Tom McBride, President, and George Hubbs, secretary-treasure.

Hundreds of excited fans drove down to the Wheeling game. Special street cars were organized to handle the crowd. The stubborn Follansbee team lead Wheeling until the last seven minutes of play. Wheeling won the game 13-7.

The Pepper Club became a colorful city tradition. In the late 1930s, the Peppers were popular for their vagabond band. Before each game, away or at home, they marched with the school band and fans through town to the football field.

The Pepper Club declined in the 1940s as World War II began. See 1939 Follansbee vs Mingo Football game.

Photo: Follansbee Brooke Co. Library